Preston Bus Station

editorial commissions

Words and photography commissioned for Blueprint magazine

Preston’s visionary Brutalist bus station was nearly bulldozed but will now be restored by John Puttick Associates, part of a wider scheme that includes a new youth centre and civic space. The imminent start of refurbishment works provided a final opportunity to record the building in its unaltered state.

To paraphrase A Tale of Two Cities, British aficionados of Brutalist architecture are finding 2016 to be the best of times and the worst of times. Birmingham’s inverted ziggurat Central Library succumbed to the wrecking ball, while Robin Hood Gardens continued to stare death ever more closely in the face. However, the ruins of St Peter’s Seminary were finally reopened to great acclaim, and work is about to begin restoring the country’s biggest bus station to its former glory, while adding a youth centre and creating a new public space, designed by John Peptic Associates.

Preston’s Brobdingnagian bus station is the largest in the UK by some stretch. It was completed in 1969 to designs by Keith Ingham and Charles Wilson of Building Design Partnership (BDP) working with consulting engineer Ove Arup and Borough Engineer and Surveyor E H Staziker. The glass-clad double-height waiting concourse – think more airport terminal than municipal bus station – is topped by five levels of car parking, expressed externally by their distinctive curved precast concrete parapets and accessed via dramatic curved ramps. At one end is a connected taxi rank, in recent years the haunt of street drinkers.

When first visiting Preston Central Bus Station and Car Park (as it is officially known), its sheer scale comes as a great surprise. “The first thing I thought when I first visited the building is that it’s very big,” recalls Puttick. “It is like a spaceship that has landed in this northern city.” Despite its monumental extent - there are 40 bays along both sides of the building, each capable of accommodating a double-decker bus – the megastructure remains concealed within the city fabric, its distinctive elevations only visible as you round a final street corner or emerge through the shopping arcade that faces-off against it. “You can definitely visit Preston and not run into the bus station,” Catherine Croft, director of the Twentieth Century Society comments. For John Puttick, there is excitement in the big reveal: “The view breaks open and you suddenly see the full length of the building. It’s very impressive.”

The entire complex is a result of post-war planning trends, intended to be accessed by pedestrian subways, which despite best efforts to keep them clean and well-lit remained forbidding, anxious spaces. As a result, over the decades, ad hoc street-level access evolved, particularly along the western side of the building addressing the city centre. Temporary construction fencing, barriers and ramps were erected to try and maintain some level of public safety, causing a sense of further disconnect from the wider city, isolating the building as an island. The dilemma persisted that unless you were prepared to take your chances in the subways, you had to hope for the best and walk across the apron in the path of lumbering buses.

Built at a time of optimism for motor transport - and growing local demand for bus stands to meet the travel requirements of the burgeoning Central Lancashire New Town region – it has since survived a nationwide decline in bus travel plus the complex fragmentation of services caused by deregulation. Preston bus station remains a busy terminal, with endless comings-and-goings of buses and coaches. Throughout the day and into the evening, the internal concourse remains busy, although the sheer volume of space means it never feels crowded. Most of all, the interior feels like it puts people first, from the generous waiting pens and bespoke curved benches to the lack of commercial intrusion, just a cafe and a few small non-chain retail concessions. “It’s a very single-minded building. We are used to having retail components everywhere we go,” Croft argues. “Preston bus station is all about going to get on a bus. It’s not even really about milling around and meeting people. It’s very determined.” In today’s socio-economic climate, this building feels dangerously socialist and democratic in its ambitions, the sort of building that appears in photobooks of communist architecture in Ukraine or Armenia. In reality, it most resembles Paul Rudolph’s Temple Street Parking Garage in New Haven, Connecticut, with similar long, split-level decks.

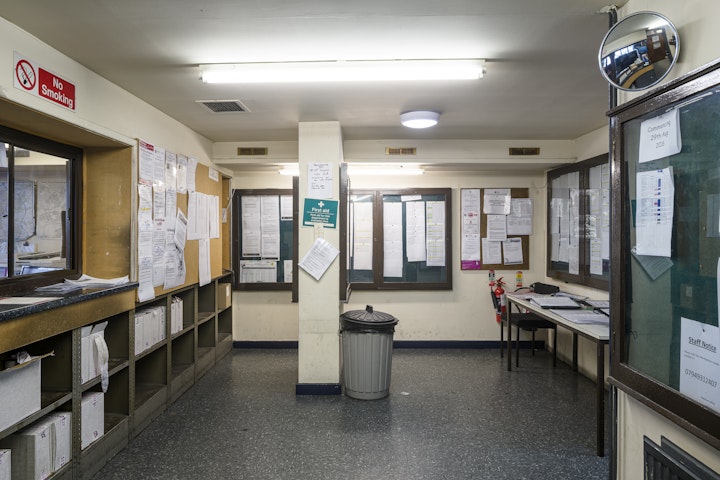

The quality of the building and its components add to the sense that the users are valued rather than regarded as cattle to be herded into trucks. “It is a very impressive building,” Croft remarks. “It still feels incredibly ambitious and really thought through, from the big ideas down to the smallest details. It’s very rigorous.” During the original design process, Ingham said that his ambition was to make the luxury of air travel available to the ordinary bus-travelling public. Puttick admires the combination of generosity of space, thoughtful signage and the use of hard-wearing materials such as oiled iroko timber planks used for the waiting pens, white tiled walls and black rubber floor. “It’s all very generous in a way that would be unusual now.”

What’s particularly remarkable is that the building remains so unaltered. “I was surprised by how intact it was,” says Puttick. “All the original signage, doors, benches are there. Obviously it’s looking tired and cluttered, the surfaces aren’t clean, the colours aren’t all original. But the main fabric is there.” A lack of investment during the last five decades means that it avoided a 1980s Po-Mo makeover or any other significant alterations. His view is echoed by University of Liverpool School of Architecture lecturer Dr Christina Malathouni, who led The Twentieth Century Society’s charge to research and protect the building. “The interior is remarkable,” Malathouni says. “Its flooring that has survived more than 40 years with minimum maintenance, as well as its elegant curved benches, are simply a joy to observe.”

Fate has looked kindly upon Preston Bus Station for long enough for us to reappraise its architectural merits, unlike other equally bold projects such as Portsmouth’s Tricorn Centre or Gateshead’s Trinity Square car park. “On one level you still need a bus station, and it does that job pretty well,” says Croft. “And land values in Preston haven’t rocketed in the same way as London. There was less to be gained from demolishing it and building something else.”

That’s not to say that the Bus Station was never under threat. For a long period during the late 1990s and through the 2000s, the local council supported demolition. In 2001, architect Terry Farrell unveiled a masterplan for the Tithebarn regeneration project which would have included obliteration of the bus station, later carried forward (ironically) by BDP. It was finally abandoned in late 2011 following the withdrawal of anchor tenant John Lewis. During this troubled period, several attempts were made to list the bus station, with growing support from local interest groups and the weight of opinion of organisations including English Heritage and The Twentieth Century Society. As late as 2012, Preston City Council was still pushing to flatten the building, arguing that much-needed refurbishment was too expensive.

A final push the following year finally saw the building granted Grade II listed status. Croft reckons this was partly due to its high profile inclusion in 2012 World Monument Fund’s list of sites at risk. “We put British Brutalism on the watchlist, and nominated three specific buildings: Preston, Birmingham Central Library and London’s South Bank Centre.” She explains that all three had been recommended for listing by English Heritage but subsequently rejected by the government. Inclusion of Preston, “put it on a par with these other buildings and elevated it to a building of international status, sending a strong message back to Preston”.

Last year, the RIBA and Lancashire County Council held an open design competition intended to secure the building’s future. The brief was to add a “Youth Zone” extension at the northern end of the bus station’s western apron, housing sports and creative facilities for Preston’s young people, while also creating a new civic space and refurbishing the bus station concourses. It was won by New York-based British architect John Puttick, whose design was not universally welcomed. Manchester Mondernist Society co-founder Eddy Rhead was quoted in the Guardian as calling the winning design “total rubbish”.

Puttick says he wasn’t overly surprised that the design proved to be controversial. Over recent decades, local passions have grown for the building. He says criticisms were largely directed at how the Youth Zone was cojoined with the bus station, a stipulation of the RIBA brief. “There was a fixation with the new building,” he says. “It’s not by any means the whole project, just one-third of it.”

Over the past year John Puttick Associates has revisited the design and made significant changes. “We developed the design for quite a while. At the beginning of the process we started to pull the Youth Zone away from the bus station,” Puttick explains. Consultation with the bus station operators, the OnSide Youth Zone charity and various heritage groups helped to focus attention on the question of whether the two buildings really needed to be connected. “It was technically complex and expensive to join them, and operationally it was clear that keeping them separate was better,” Puttick says. “Heritage groups were also happier for us to move the new building away, it respects the listed building.” As a result, the new design is less complex and more affordable that its predecessor.

Cutting the new building adrift from the main bus station retains uninterrupted views along the dramatic 170m-long western elevation. It also provided Puttick with an opportunity to revise comprehensively the design for the Youth Zone. “It wasn’t just about pulling the existing design away from the bus station. There were a new set of parameters for the Youth Zone, it was now a different thing. We completely revised that component.” Puttick is clearly proud of his new design, even if some locals were shocked at how different it was from his original vision which had won both the RIBA competition and a public vote. “A competition is the beginning of a process, not the end,” rebuts Puttick. “You shouldn’t be handcuffed to what you started with.”

It’s fair to say the new 2,600 sq m design has been far more warmly received than its predecessor. Its stepped form, topped by an open-air football pitch, is clad in blue zinc, sitting atop a 1m-tall concrete base. The tallest volume - the sports hall - has been pushed as far away from the bus station as possible, the remainder of the building stepping down towards a new public space. “We step back as the bus station cantilevers out,” observes Puttick. “It creates a hierarchy for the site. The bus station remains an extremely powerful building. Our building does not compete, but still feels confident and important for young people.” Internally, a glazed entrance hall leads to a central activity space, with views through to different sports and creative pursuits taking place within other areas.

The first phase of the £23 million project, to refurbish and repair the bus station and car park has received Listed Building Consent and will start imminently. Puttick explains that little will change internally, although the original dark grey colour scheme for timber work on the upper level of the interiors will be reinstated, a new central information point incorporated into the concourse and the southern end of the building turned over to being a coach station, separated from the rest of the concourse by a glass screen that stops short of touching the coffered soffit and externally utilising the disused taxi rank.

The double-height perimeter glazing is to be repaired and strengthened to meet contemporary wind loading standards and lighting throughout will be overhauled, integrated into the building in the spirit of the original design, rather than the present surface-mounted ceiling lights. New entrances will replace some of the original sliding timber doors, which despite their utilitarian beauty have always been difficult for people to move. The bus station’s famous sans serif British Railways-style signage, fabricated in GRP, will be restored and the futuristic analogue/digital clocks returned to working order.

Along the western side of the building, existing waiting pens will be removed as they are no longer required. However, “there will be no additional new retail spaces, no bulking up the space. It will be very much like it is now,” pledges Puttick. Most obviously will be a decluttering of signs, lights and other detritus that has accreted to the structure over the decades. “We are taking it back to 1969, while inserting some new functions.”

The final piece of the three-part jigsaw, due for completion in 2018, is the creation of a new public space addressing both the bus station and the Youth Zone while also providing new pedestrian connections to the City Centre. The ambition is to provide a flexible space for markets and other outdoor events, with softer landscaping along the western edge which “hardens” as it gets nearer to the concrete and glass of the bus station. It will mean that those forbidding subways can finally be closed for good and it will be much easier for travellers and Brutalism fans alike to access the building.